I walk up to the reception desk at Albany Medical and say, “I have COVID.” I do not say, “I think I have COVID,” because at this point I am certain.

Continue readingSacred Black Space

TMI Project’s Black Stories Matter program is a sacred space. Sacred is the only word that comes close to describing how it feels to me. This is in part due to it being a space for people to be vulnerable, to share their truths and their stories. But, more than that, it is Sacred Black Space, of which there are too few.

Continue readingBenny Eichert

“Why do I still feel like a fraud? Like I don’t belong. Like I’m not black enough.“

Racism has been a big part of my life, I just never acknowledged it. I hate stuff like this. It makes me uncomfortable, as I’m sure it makes a lot of us. It’s easy to make excuses and look away. But something this morning is calling me to confront this feeling. Two more lives were lost. Another black man and another black woman to add to a huge list of those taken by people who are supposed to protect and serve us. There is something wrong with America. And it’s not just COVID 19. Racism has been here for a lot longer.

A year ago, I did a DNA test. I read it and was stunned. I’m 1/4 Portuguese and 1/4 Spanish. I’m 27.1% African from Northern and Western Africa. Why do I still feel like a fraud? Like I don’t belong. Like I’m not black enough.

I was adopted by two Caucasian people. I was told I was Hispanic and Italian. I don’t blame them for this misinformation. It’s very possible that my biological mother, whom I never met, didn’t know who my father was. I had 6 other adoptive siblings. Five were African American. I never felt I belonged. But, we all dealt with a lot of racism early on.

I was called a Spic and nigger in first grade.

I was told my real parents didn’t love me.

I was targeted by teachers and classmates because of my white parents.

I had a barber tell me that he didn’t have clippers for “my type of hair.”

I was looked at differently because of my color.

I feel a pain in my heart. A chill in my skin. I can’t describe it. I reach down at my chest where my heart is and feel something wet and warm. I raise my hand and see pain and hurt. It is like a dark moonless night. I don’t know why I thought if I ignored it long enough eventually I would be okay.

My art has called to me to create from this pain. It is one place I cannot hide what I feel. My art is real, honest and painful. Sometimes I hate it for this reason. But, my art has led to such growth in my life. It’s an outlet where I can say I am sorry to the younger version of myself for not validating this pain. I am sorry for not acknowledging my place in this fight.

I am a puzzle with a lot of different pieces.

I am Portuguese, I am Spanish and……

I am Black.

This story was received as an online submission.

Want More Black Stories Matter Content?

Stories have the power to increase visibility, raise awareness, change people’s hearts and minds, and inspire people to take meaningful action. We are making every effort to ensure all of our Black Stories Matter content is easily accessible, widely consumed, and is accompanied by tools to deepen the impact.

Listen: The TMI Project Story Hour, Season Two: Black Stories Matter, launches this fall. Learn more and subscribe to our podcast HERE

Host: a Black Stories Matter viewing party and discussion from anywhere in the world. Click HERE to learn more and sign up.

Share: TMI Preoject’s mission with Black Stories Matter is to elevate the underrepresented stories of the Black experience in America – the full spectrum – the triumphs, humor, beauty, and resilience. Click HERE to submit your story to be featured on the TMI Project blog.

Jaggar Harris

“The American dream — the dream that makes you believe you can have equality and the same opportunity available to any American — is a nightmare for me because I’m Black.”

After watching the horrifying and brutal killing of George Floyd on national TV I cried. I was deeply sickened. I wanted to do or say something that would help others understand what it’s like to be Black in America because racism not only exists in the police departments, the criminal justice systems and the government, it exists in the workplace too.

During my eighteen-year career in higher education, which spanned from 2001 to 2019, I was the victim of racial discrimination four different times by three different employers in four different cities in the states of Colorado and California. The American dream — the dream that makes you believe you can have equality and the same opportunity available to any American — is a nightmare for me because I’m Black.

The first time I was discriminated against was in 2001. I was terrified and didn’t know what to do. My friends said, “Don’t fight. You’re just one person and nothing you do will make a difference.” My family said, “Don’t fight because if you make waves you’ll lose your job.”

But after years of being harassed, humiliated, and stripped of all dignity, confidence, and strength over and over again, I stopped hearing everyone around me and started listening to God. God inspired me to speak my truth no matter how painful it was and to do my best to prevent others from experiencing the devastation to their lives and careers that I had painfully endured.

I fought back against the first employer and each subsequent employer. When they realized that I had documentation that could prove the severity and frequency of the discrimination I endured, each one paid me hush money to buy my silence and hide the racism in their organizations. They also blackballed me from the industry that I loved, in the city that I worked, so I was forced to relocate and start over. Each time, I moved to a different city hoping to get hired by a company that was free of racism and, sadly, I found that in America no such place exists.

I’m tired. My battles against racism in the workplace that I have been forced to fight for the last eighteen years have left me broken, traumatized, and emotionally spent. At 52 years old, I’m getting too old to keep starting over. Even worse, I’m witnessing my children, who are now all grown up with careers of their own, suffer the same fate and it’s heartbreaking. It’s heartbreaking.

I share my story about fighting back, not only to help me deal with the trauma of racial discrimination, but also in hopes that it will make a difference, for my children and others.

This story was received as an online submission.

Want More Black Stories Matter Content?

Stories have the power to increase visibility, raise awareness, change people’s hearts and minds, and inspire people to take meaningful action. We are making every effort to ensure all of our Black Stories Matter content is easily accessible, widely consumed, and is accompanied by tools to deepen the impact.

Listen: The TMI Project Story Hour, Season Two: Black Stories Matter, launches this fall. Learn more and subscribe to our podcast HERE

Host: a Black Stories Matter viewing party and discussion from anywhere in the world. Click HERE to learn more and sign up.

Share: TMI Preoject’s mission with Black Stories Matter is to elevate the underrepresented stories of the Black experience in America – the full spectrum – the triumphs, humor, beauty, and resilience. Click HERE to submit your story to be featured on the TMI Project blog.

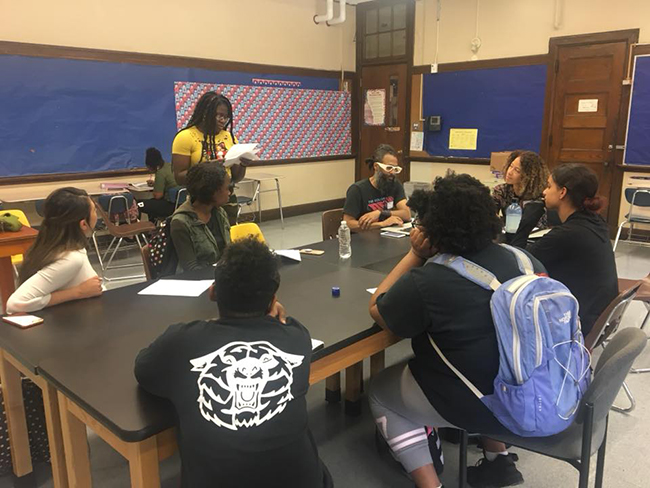

Black Stories Matter workshop leader Dara Lurie takes us inside an intergenerational storytelling workshop

– Dara (she/her)

TMI Project’s Intergenerational Black Stories Matter Workshop took place on February 17th, a brisk, beautiful Sunday afternoon, at the A.J. Meyers-Williams African Roots Library in the historic Ponckhokie Kingston neighborhood.

Turnout was exceptional – there were 17 participants ranging in ages from the youngest at 14 to the eldest being as library director, Odell Winfield, put it, ‘of the ‘50’s generation.’

My co-facilitator, Micah (he/him) and I sat in the middle of the long table constructed of 3 or more tables placed end to end. Just as we were about to get started, Shawaine Davis (she/her), one of the Black Stories Matter Storytellers from Kingston High School arrived with several friends.

In 2018, the original cast of Black Stories Matter, myself included, performed for all 2,000 Kingston High School students. Hearing our stories inspired Shawaine, along with eight other students to participate in the first-ever teen version of a Black Stories Matter workshop culminating in a performance at the Kingston High School.

Shawaine was not particularly outspoken when she showed up to her first workshop session last year but she was determined to tell her story. And tell her story she did, with a vengeance.

The first line of Shawaine’s story reads:

‘Lord give me patience because if you give me strength, there’s no telling what I might do,’

and it only gets better from there.

On this afternoon nearly a year later, Shawaine strode into the library with an air of purpose. Having been through the process of finding and telling her story, she seemed to be encouraging her friends to do the same. They all took seats at the far end of the table and quickly settled in.

Micah outlined the idea of the workshop – that black stories come in all shapes and sizes – they are as varied and diverse as the people who embody them. “If you’re a black person writing about learning to tie your shoelaces, that’s a black story,” Micah joked. The truth underlying his joke is that we are all ready to expand beyond the ‘stock’ or expected stories of blackness that always define us in terms of struggle and oppression. It’s time to uncover the beautiful, complex and surprising counter-stories of black American creativity and resilience.

And that’s what everyone at this table had come to do, explore the real stories from their lives, listen to the stories of others around the table and learn something new about their own perspective.

The 14 –17 and 20-something crowd was seated to my left, with the age gradually rising into the 30’s, 40’s and beyond at the other end of the table. True inter-generational representation.

As we do in all TMI project workshops, we offered prompts to help participants focus their thoughts. Some of the prompts offered for this workshop included:

How racism has affected your self-esteem, social status, physical or mental health.

Another prompt:

What you love about being black and/ or black culture.

Some used the prompts and others wrote freestyle about an experience that had profoundly shaped their life.

Patterns emerged from diverse stories. One young man wrote that despite his experiences of being bullied in school, he continues to value himself, knowing that he is someone who has a lot of love to give. He also affirmed his determination to sharpen his basketball game.

Another participant, also a student at the Kingston High School, addressed a person who has bullied her, writing: ‘Go ruin someone else’s day, boo boo…’

At the other end of the table, a woman wrote about bullying that she’s experienced working in the corporate world. This kind of bullying came in more subtle forms of disrespect from colleagues that worsened as she gained greater power within the organization.

Yet another participant wrote about the challenges of parenting biracial children.

We had time for two rounds of writing and sharing. Three or four participants raised a hand to read something out loud during each of these segments. We reminded everyone of a TMI workshop rule: No negative preamble. This sets a tone and an understanding that we are all there, taking turns as writers and audience, to affirm, support and encourage each other in this amazing process of discovering our true stories.

At one point during the workshop, looking in either direction, I felt that I was seeing a beautiful landscape of the faces and stories assembled at the table. These two hours felt like a sacred moment. It occurred to me that each person at the table had come to add their piece to a collective history that is just now beginning to be written.

I thought about the experiences the Kingston High School students wrote and shared in workshop – stories of being told ‘you don’t speak black’ or ‘you don’t act black,’ stories about being judged for their hair or complexion, constantly being reminded that as a black person you are always under a critical white gaze. I remembered my amazement, realizing that in the four decades since my own teen years, racism really hasn’t changed at all.

As Audre Lorde wrote:

‘At a quarter to eight Mean Time, we were telling the same stories, over and over and over…’

Or, maybe something is changing. When I was their age, no one asked me what it felt like growing up as a biracial person. I had no one to speak with about my experiences. These students were not only able to articulate their stories, but they also got up on stage and told their stories. And they weren’t alone. They were part of a group of storytellers each one risking vulnerability to bring their truth to light.

Something I know from my own life is that black people are a diverse & resilient people. With a little bit of space and encouragement to tell our stories, we’ll make them better, clearer and more powerful as we bring them into resonance with a collective understanding that’s emerging.

At one point in the workshop, one of the participants took a deep breath and began ‘What happened was….’

In the same instant, Micah and I looked at each other with big smiles.

We knew we had just found another prompt!

– Dara Lurie, TMI Project Workshop Facilitator

A Conversation with TMI Project’s Black Stories Matter Workshop Leaders Dara Lurie and Micah

TMI Project staff recently read Ijeoma Oluo’s So You Want to Talk About Race. Why do you think race is such a tricky topic?

M: The concept of race is one of the greatest tricks that we’ve ever fallen for. It was designed to make sure the minority who had power kept that power. If all poor people realize how much they have in common, the power structure will change. Racism was created to say to the poor, white person, “Hey, you’re better than those black people.” It’s based on economics and power. And so the whole thing unravels if you talk about it. Not just race as a system of oppression, but all power structures unravel if you tease out this question of, “Who has power and why?”

D: If you’re black or a person of color, it’s not hard to talk about it. That is all we ever think and talk about to ourselves. “What the f**k is going on?” is what we’ve been saying as long as I’ve been around. It’s that secret conversation you have among other people of color or with a few trusted white friends. But it’s not something you ever bring out into the wider discourse. Because the conversation always devolves into, “Who pays for things? I didn’t do anything wrong. Why should I be responsible?”

Above: TMI Project Workshop Leaders Dara Lurie (she/her) and Micah (he/him) teaching a Black Stories Matter workshop to students at Kingston High School.

In your opinion, how can we use initiatives like Black Stories Matter to tackle systemic racism within our systems of power? Aka: How can we take something that’s so emotionally-charged and turn it into policy change?

D: I’m reading the book My Grandmother’s Hands right now. The author Resmaa Menakem is a somatic therapist, and he talks about the trauma that was “blown into the African bodies by the white colonizers and slave owners.” But also the trauma that white refugees from Europe brought with them. They brought punitive systems from England where people were taken to the gallows, lynched and flogged. This unmetabolized trauma was held within the European settlers who then blew it into enslaved Africans. Menakem says the solution to systemic racism is within the body. That resonates with me. It needs to be felt in the body – and storytelling is one way we reach that understanding.

M: I understand the desire to answer questions like, “What more can we do? What are the next steps?” But the simple power of saying “Black Stories Matter” should not be underestimated. I was talking about it with my son [Gopal Harrington] today because he’s going to read at the Stories from Across Generations show on February 16th, and he said, “My story’s not a black story.” And I said, “You’re black. And you have a story. Therefore, it matters.” That’s what we mean when we say “Black Stories Matter.” We’re saying, “Here’s my black story, here’s how I was impacted by race, here’s what a racist said to me.” It doesn’t matter if your story is about tying your shoes. Your story matters because you’re alive and all black stories matter.

D: The statement “Black Stories Matter” is a statement that nobody’s saying because history has told us that black stories don’t matter. And we’ve all believed it.

M: We all think, “Nobody wants to hear my story.” White. Black. Whatever. But there’s that extra layer for those of us who are black. We recently had to change venues for Stories Across Generations to accommodate more audience members due to demand. So a bunch of white people are effectively saying, “We do want to hear black stories because Black Stories Matter.” We’re changing the narrative, and it’s hard to believe that all these people actually want to come out and hear us tell our black stories. That shit blows my mind.

I read this article the other day, “All black stories matter, not just ones in struggle,” and this resounds so much with what you’re talking about.

D: We’re not looking to tell stock stories of blackness. That’s been done enough.

M: What it boils down to is this: I don’t know the full answer to your question. We should be holding it loosely anyway. TMI Project is naturally evolving. We’re working with high school students, we’re going digital, we’re expanding. If the issue at hand is how we share power, relinquish power, take power, then we’re doing it right because we are collectively figuring out how to share this power and where the Black Stories Matter initiative organically goes next.

This just makes me wonder: what can participants expect of the upcoming Black Stories Matter storytelling workshop on February 17th (the day after Stories from Across Generations)?

D: TMI Project has a really strong methodology and approach to helping people find where their stories are hiding. Some people come in with ideas, and that might be part of the puzzle, but with the writing prompts and exploration, they figure out the rest. Don’t expect to know your story when you first arrive. The workshop opens pathways for people to find their stories, whether they’re coming from a sense of knowing, a sense of curiosity or a sense of yearning.

M: There are a wide range and breadth of stories, not just ones of struggle. At its heart is the fact that all people who aren’t white men have, in some way or shape or form, at some point, been made to feel less than human. It’s important that we connect to the parts of people’s stories that are human and universal. For black people taking this workshop, they can expect to experience a methodology that will help them tell their story. Whatever it is. Because most of our stories are wrapped up in shame, fear–

D: –anger, and guilt–

M: — and guilt. It helps to have somebody else hold a space for you so you can get your story out there. And black people, especially those in the Hudson Valley, don’t have that many spaces. So this workshop will be that space.

Why couldn’t I be black and be the true me?

Callie (she/her)

Thinking back over her own difficult journey with their racial identity, Callie ponders the question, “How can I help my daughter feel proud of her own blackness?’

#blacklivesmatter #blackstoriesmatter #defendblacklives

I hated black people for a while. I felt they judged me for being me. And I was trying so hard to figure out who I was. Did I need hoop earrings and air force ones to be black? Did I have to to do my hair and nails? Why couldn’t I be black and be the true me?

My 9-year-old daughter recently said to me, “I wish I could be a beautiful black woman, Mommy.” She’s very fair, and I often feel guilty at how relieved I am that she can, “pass.” I want her to be a proud black woman, but I also don’t want her to suffer through what I went through as a black girl, and woman, not fitting in.

I moved to Wilton, CT, an all white town, when I was 8. On my first day of fourth grade, a boy on the bus called me a nigger. I didn’t know what that was, but I knew it was bad. I told my principal, and he was appalled. His response – have me teach the school about Kwanzaa. He wanted me to explain different holidays from “my culture” to a school full of white people. I didn’t even celebrate Kwanzaa.

What was it like being the only black kid? Well, for starters, every day people told me I wasn’t really black. As far as they were concerned, black people were “gangsta” or spoke in ebonics, listened to rap music and wore hoop earrings. My whole life, everyone I knew, convinced me that I wasn’t one of those “homegirls”. They mocked ethnic names, and talked about the “hood”. As far as I was concerned, I wasn’t black either. My mother only had white friends. I only had white friends.

People thought I wasn’t black because I wasn’t that hoop-wearing homegirl. I began to believe that, too. I wasn’t black. I wasn’t white. What was I? I tried so hard to be “white.” I began to hate BET. I wore bell-bottoms and tie-dyes, listened to The Grateful Dead and The Beatles, while still being followed in stores.

When The ABC Kids, nine black boys from inner-cities, came to my high school, suddenly, everyone assumed they would be my best friends. But, they mocked me. The same things that made the white people accept me, separated me from the black people I finally had an opportunity to interact with. The black boys hated me because I was a poser. I wasn’t black. I wasn’t white. But, who was I?

I hated black people for a while. I felt they judged me for being me. And I was trying so hard to figure out who I was. Did I need hoop earrings and air force ones to be black? Did I have to to do my hair and nails? Why couldn’t I be black and be the true me?

Now, many years later, I’m an activist and an organizer for social justice. As a leader, my job is to call people in and help them understand institutionalized or systemic racism. I can do that. I can use my voice and position of power to explain to white people how offensive or hurtful they are. I can explain that their privilege is more than not being called a nigger. It’s feeling safe when going to doctors who aren’t racist toward them. It’s knowing teachers aren’t racist towards their children. I can explain hard things, lead marches, scream into a megaphone, train young leaders and work to create change. And while it’s a challenge, I’m capable of doing these things.

What I don’t know how to do is make my daughter proud of her blackness. How do I make her proud while simultaneously trying to protect her from being pulled over in parking lots and followed in stores? I’m not sure. I guess I still don’t know what being black means, so how do I teach my daughters?

Want More Black Stories Matter Content?

Stories have the power to increase visibility, raise awareness, change people’s hearts and minds, and inspire people to take meaningful action. We are making every effort to ensure all of our Black Stories Matter content is easily accessible, widely consumed, and is accompanied by tools to deepen the impact.

Listen: The TMI Project Story Hour, Season Two: Black Stories Matter, launches this fall. Learn more and subscribe to our podcast HERE

Host: a Black Stories Matter viewing party and discussion from anywhere in the world. Click HERE to learn more and sign up.

Share: TMI Project’s mission with Black Stories Matter is to elevate the underrepresented stories of the Black experience in America – the full spectrum – the triumphs, humor, beauty, and resilience. Click HERE to submit your story to be featured on the TMI Project blog.

Jordan

My Blackness has come to mean my power. I walk into a room, and everybody notices my beautiful melanin-rich skin. The white folks try to impress me with their knowledge of shoes or basketball, both topics I know nothing about, but regardless they seek my approval. They are astounded by how my hair defies gravity and resembles the texture of the bushes and trees that make up our extended family, my skin the tree bark. Mother Earth is a Black Woman. The sun kissed me when I was born, and I am reminded every day it will never hurt me. My culture is magnetic. It’s irresistible. It brings out the true expression within all of us. My Blackness is stylish. It corresponds with all the latest trends and fads of the time. I woke up like this. My Blackness is resilient. My Black don’t crack. Like fine wine I look better with age, the fierceness of my glow grows stronger with every decade, as my people’s impact on the world gets stronger every century. My Blackness is Love. Just like when the passion bubbles up inside and comes bursting out, I cannot hide my Blackness. Some embrace it, others run away from it, not because it is inherently good or bad, but because it is powerful. My Blackness is nurturing. My Blackness is real. My Blackness tells a truth that some cannot handle. My Blackness is beautiful and never ceases to amaze me.