BY EVA TENUTO

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, TMI PROJECT

Yesterday, on Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday, TMI Project participated in an amazing initiative, Writers Resist. “Writers Resist is a national network of writers driven to defend the ideals of a free, just and compassionate democratic society.” Events took place all over the nation and in countries around the world. The local event that we participated in was held at The Bearsville Theater in Woodstock NY. The house was packed all afternoon. Every writer/reader/performer brought something important to the stage. The day left us feeling connected, and in turn, hopeful.

After our set was over, I was asked if my story/announcement was anywhere in print. It is here below.

If you would like to hear Tameka Ramsey’s story, please join us at Black Stories Matter, in Kingston NY at 7:30 pm on Saturday, March 25th. Location TBD. Save the date. Details to follow.

*******

TMI Project is a non profit organization offering transformative memoir writing workshops and performances. We believe that when storytellers divulge the parts of their stories that they usually leave out — the parts they are too ashamed or embarrassed to share, they become agents of change, fostering greater understanding and compassion among people. Our work is intentionally transformational and used to incite social change.

Since 2010, TMI Project has worked with incarcerated teens, teen moms, veterans, international gender activists, adults with mental illness, domestic violence survivors and many other populations who don’t often have a chance to tell their stories or be heard. TMI Project’s work has impacted the lives of the more than 1,400 people who have participated in our workshops and more than 12,000 people who have listened to our stories.

Now, as an organization, TMI Project is addressing the issue of racism in America.

We started talking about how our organization could respond to this issue in 2012 after Trayvon Martin was brutally murdered at 17 years old. We had many brainstorming sessions with one of our board members, Tameka Ramsey, about how we could participate in the solution. But our organization was young and we didn’t yet have the capacity and it got put on the back burner, again and again.

Then Eric Garner was killed. Then Michael Brown was killed. Then 12 year old Tamir Rice was killed while playing on the playground. Have you ever seen pictures of Tamir Rice? I have and he resembles my nephew, Miles, the child who stole my heart the second he was born.

A few weeks after Tamir was senselessly murdered by Cleveland police officers, I was taking my then nine-year-old nephew Miles and his friend John to one of those horrible bouncy parks in the mall. Like Tamir, Miles is an adorable brown boy with sweet brown eyes and irresistible cheeks. His friend John is equally cute with blond hair and blue eyes and about a head shorter than Miles. Miles is tall for his age.

In the car ride over, they talked seriously about Pokémon, speaking a language I couldn’t understand, and snacking on fist fulls of Cheez-Its. When we arrived, they had to be reminded to be aware of parking lot traffic, as they carelessly bounded out of the car. They entered the mall in true little-boy spirit, jumping from one colored floor tile to another, trying not to land on any white ones (or in their world, trying not to fall into the red-hot lava). When we passed Citizen’s Bank they thought it was funny to rename it Cheez-It Bank. Both boys pulled up the hoods of their sweatshirts, stuffed their hands in their pockets to look like they were carrying guns, ran up to the bank entrance for a pretend stick-up and yelled, “Give me all your Cheez-Its!” Then they quickly ran away in side splitting hysterics. While watching them dive head first into what should have been a carefree world of make believe, my heart dropped. Tamir was killed while playing with a fake gun on the playground.

Miles and John started to run away. They looked behind to see if I was going to let them go any further. On other outings, I’d often let them walk far ahead, as long as I could see them, so they could feel independent. But on this particular day I stopped them in their tracks.

“Boys, come back.” As they walked toward me, I had my first glimpse at the way the world would soon be receiving Miles as he transitioned from a cute little brown boy to a young strong black teenager. His sweatshirt all of a sudden a hoodie. His existence, no matter how innocent, somehow perceived as a threat. “Listen to me. This is important.” I waited until Miles was looking directly at me. “You can never pretend to be carrying a gun. Ever. A little boy was just killed by a police officer and all he was doing was playing with a fake gun on the playground.” This information was received with the disgust it deserves, the alarm we no longer have because of the frequency with which we hear these stories. But this was their first story. They could not believe their ears. “A police officer killed a kid?” Miles asked. “I thought they were supposed to protect us.”

As kids do, they quickly forgot what I had told them and as soon as we reached the horrible bouncy park, refocused their energy on a game of tag. But I couldn’t let it go. Did I do the right thing? Is there anything I can teach him that will actually protect him?

Be strong. Be quiet. Be submissive to authority. Stand your ground. Don’t ever break the law, not even a little bit. Don’t play that game. Don’t wear that sweatshirt or drive that car or listen to that music.

In the end, none of it matters because black boys aren’t being killed because of their fake guns or sweatshirts. They’re being killed because they’re black. Will there ever be a generation of black children who can grow up in this country and actually experience what it means to be free? Freedom to play, explore, come into oneself, to thrive, to be safe?

After Tamir Rice there was Walter Scott, Freddie Gray, the six women and three men gunned down in their place of workshop in South Carolina, Sandra Bland, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, among countless others.

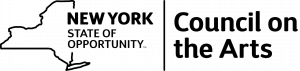

Tameka and I met again, with fear for the future and an overwhelming feeling of powerlessness. After many conversations, more brainstorming, one Sunday school session and a baptist church service, we partnered with everyone on staff at TMI Project, created a diverse committee and launched Black Stories Matter.

Black Stories Matter is TMI Project’s way to participate as an organization in the national outcry of injustice. #blackstoriesmatter will be a digital campaign, so we can use our platform to expose inequality and injustice rapidly and frequently through true storytelling. It will also be a live event, featuring the stories of 10 writers of color, held on March 25th at 7:30pm in Kingston, NY. We’re still confirming the location but please save the date. We hope you attend and listen. Listen with your child-self, like you are hearing your first story of injustice, and let yourself feel the outrage it deserves. Let the stories call you to action.

White people don’t talk about race because we’re afraid we’ll get unintentionally caught, that we will uncover our own discreet racism by saying the wrong thing, that our blind spots will be pointed out. I think the best thing we can do is welcome the insight, be willing to view our unintentionally racists points of view and then work actively to replace them with informed knowledge, deepened compassion and active commitment to work for justice for all. It’s time to speak up. Take risks. Let go of privilege. Use what’s left to a eradicate racism. Fight for black lives. They matter. They wholeheartedly matter.

Here, to share an excerpt of one of her stories, is Tameka Ramsey, whose leadership has helped bring this initiative to fruition.

*******

By February 1st our website will be set up to accept story submissions from around the country for our digital campaign. Stay tuned! www.tmiproject.org

This initiative would not be possible without the partnership of Alliance of Families for Justice, Center for Creative Education, Pointe of Praise Church, Hudson Valley Families Against Mass Incarceration and ENJN. If you are interested in partnering or getting involved, please email blackstoriesmatter@tmiproject.org.