A disturbing finding in leading TMI Project true storytelling workshops over the past 8 years is the prevalence of sexual abuse among our participants. Early on, I noticed if one person shared a story about sexual violence, inevitably, others would chime in. What I didn’t realize until a year ago, is what they were saying to each other was: Me too.

This past October I presented Tarana Burke, founder of the #metoo movement, with the Eleanor Roosevelt Medal of Honor. I believe she was the best person to receive this award at this particular moment in history and I was deeply honored to present it to her.

My world and the world of women across the globe shifted dramatically when a small hashtag with a big history took over the internet like wildfire. #metoo unleashed a pent up fury, an outpouring of stifled shame that didn’t belong to us. We were given permission to break our silence, to share our most difficult stories, not alone, but in droves. We’ve since been held and supported by each other instead of blamed and not believed

An eruption of this magnitude is not created in an instant. For more than 25 years, Tarana Burke’s unrelenting dedication to creating empowerment through empathy for those impacted by sexual violence, has been laying the foundation for this movement, now strong enough to hold us all.

Like many women, I was personally impacted by the #metoo movement. I had buried memories that needed uncovering. In that uncovering, I realized that one experience, which for decades I had convinced myself wasn’t that bad, was actually rape. The more stories I hear, the more memories come back, the more I find myself saying, “Me too.” I realized, as a survivor, I never listened to my body or trusted my instincts. The #metoo movement gave me permission to talk and to write about what happened to me. I now understand the power of intuition held within my own body.

My community has also been impacted by the #metoo movement. Collectively, we talked about things we all knew but never gave voice to. We joined forces and faced our fears about speaking truth to power. Like many others, we also faced consequences for speaking out, and dealt with more harassment for stepping forward. But, we got stronger and made it clear that men and women abusing their positions of power would not be tolerated in our community.

I recently heard Tarana say, “I never thought I’d see a sustained national dialogue about sexual violence, but here we are, which lets us know anything is possible.” I believe her. I believe survivors. I believe anything is possible. I also believe that after dialogue, action is required. I hope all of us here today will renew our commitment to keep fighting for those most impacted, to keep our focus on the healing of survivors and to end sexual violence once and for all.

I recently heard Tarana say, “I never thought I’d see a sustained national dialogue about sexual violence, but here we are, which lets us know anything is possible.” I believe her. I believe survivors. I believe anything is possible. I also believe that after dialogue, action is required. I hope all of us here today will renew our commitment to keep fighting for those most impacted, to keep our focus on the healing of survivors and to end sexual violence once and for all.

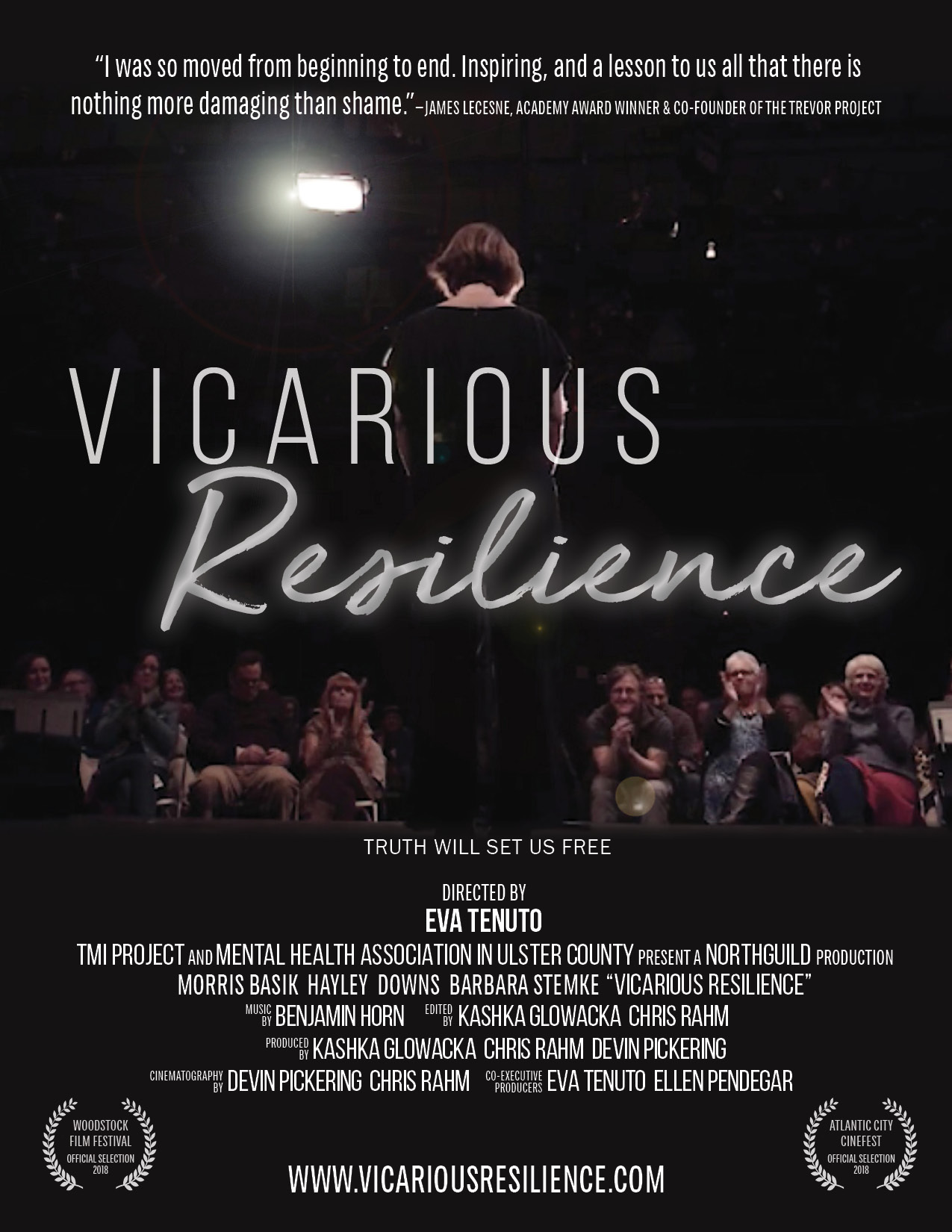

– Eva Tenuto, TMI Project Executive Director & Co-founder

If you are interested in joining the #metoo movement, check out their new website. If you’d like to share your story with the TMI Project community fill out our online story submission form.

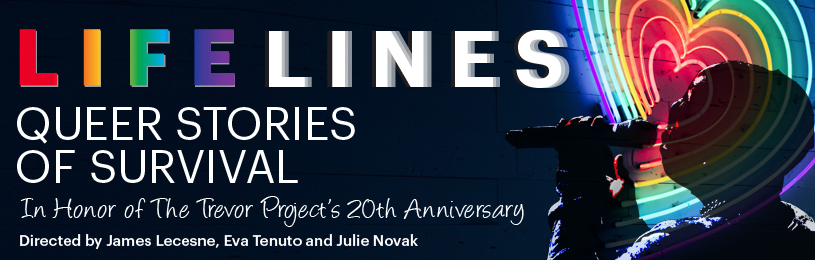

To that end, TMI Project is bringing

To that end, TMI Project is bringing