In the face of racism and the daily microaggressions churned out in a white world, Zanyell (she/her) spends years starving herself and self-harming in an attempt to disappear until she finds yoga and starts to feel more comfortable taking her rightful space in the world.

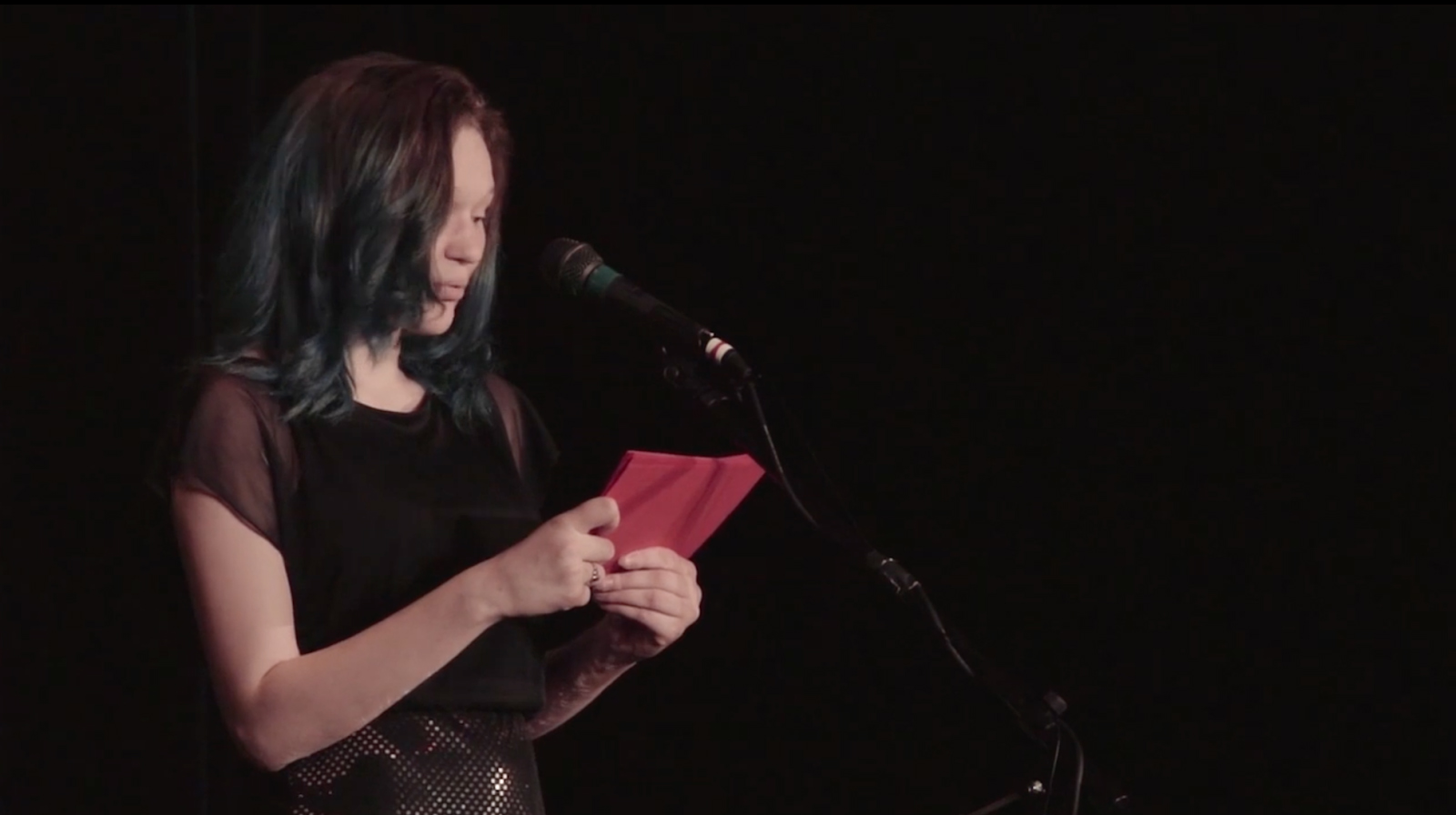

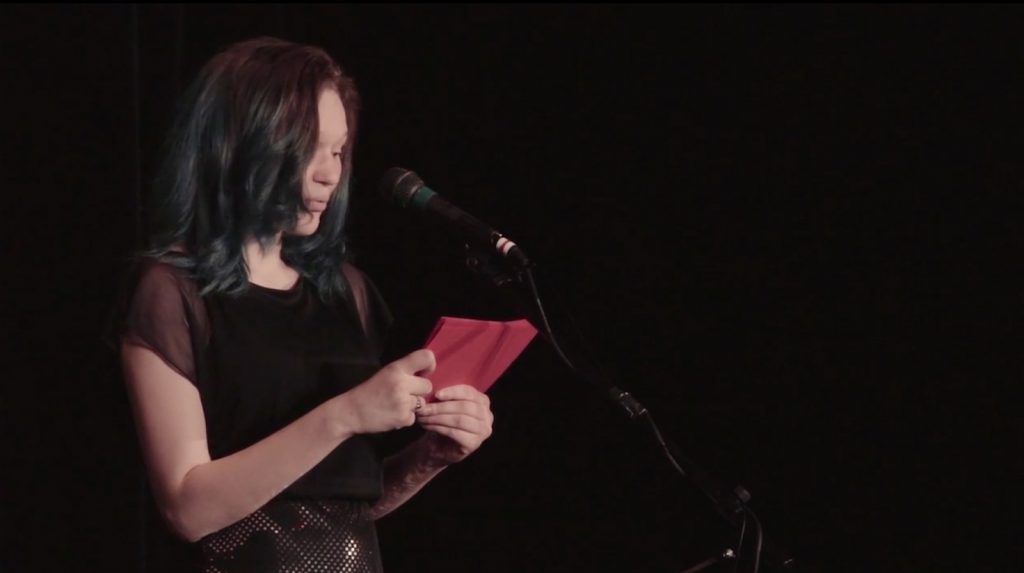

Storyteller Zanyell Garmon wrote and performed our Story of the Week as part of TMI Project’s newest Black Stories Matter true storytelling performance Black Stories Matter: Truth to Power, which was presented at Pointe of Praise Church in Kingston, NY on June 21, 2019. Read on below.

The air is humid, my skin still damp from swimming in the creek. My arms are swinging, feet skipping in time with my friends. I’m about ten or eleven years old. I smile and feel a sense of belonging, like in my favorite movies when you’re with your group of close friends.

Then, one of my friends turns back to look at us and laughs.

“Zanyell, it’s so dark I can’t see you,” he says.

My other friends either laugh or stay quiet. At first, I don’t understand what he means, but when I do, I fall silent too. It isn’t a conscious thought in the moment, but I know that this is when I decide I don’t want to be seen; not for my blackness.

I start to worry about how I look, how I act, and how I’m perceived. My mother tells me I have to work twice as hard because I’m black and a woman. It’s exhausting, but it soon becomes an obsession. In high school, I get called an Oreo because I speak white and listen to the wrong music. I’m placed on the honors track with mostly white students and I’m told that I act like I’m “better” than my black friends. Black and white beauty standards are also different. My mother praises my curves and my “J-Lo” booty while my white friends often ask me if their butts look big or their hair is too poofy.

I watch America’s Next Top Model and see thin women with straight hair and straight teeth. On the dark web of Tumblr, I re-blog women with thigh gaps and protruding ribs, straight hair, and sunken in eyes. I fantasize about what it would be like to be them.

In a chat room where we talk about anime, I use a picture of a blond white anime character, as my avatar. It takes me a couple months to think, oh wait, I’m lying. I don’t look anything like that.

In real life, I wear extensions and perm my hair. I skip meals to lose weight. The first day of high school, after I starve to lose almost 30 pounds, my friends say, “You look so good!” At 99 pounds, I have achieved my original goal, but I still feel like I take up too much space. Ultimately, I want to disappear.

I meet Caitlin online. She’s bulimic and self-harms like I do. The cutting help us control the pain of overwhelming emotions. It’s the intense shock of that pain, cutting into the flesh and drawing blood, that distracts from the feelings we can’t handle. I feel like she’s the only one who understands. We starve together, compare our calorie intake, offer support on the days when we felt weak. We promise that we’ll get better together.

“Don’t die on me Cait. We can do this,” I tell her too many times.

Her grandmother sends her to mental hospitals, deletes her accounts, and takes away her phone but she always finds a way to talk to me again, texting me from new numbers and messaging me from new blogs.

The last time I speak to her, she is withering away, 86 pounds at 5 feet 11 inches. And then, when I’m in 11th grade, Caitlin disappears. I have no way to contact her, no last name to look up. I search for her for a year and can’t find her. Just like that, she disappears. I decide I will not disappear like Caitlin.

A friend brings me to a yoga studio. The teacher is black. It’s a very diverse and authentic yoga studio. Doing yoga makes me feel better.

I spend a month in an ashram in Nepal training to become a yoga teacher with other American trainees. We practice yoga three times a day and three times a day, eat the same meal of rice, dal and roti. Eating is difficult for me at first. I cry a lot and everyone in my group is supportive. They are like a family to me. I realize that I’m eating with people who genuinely care about me and that this food is meant for me to eat. I begin to take up more space in my own body.

One day, we all walk an hour to buy ingredients for a chocolate cake. We make the cake and everyone eats it. The workers at the ashram eat the cake. Even I eat the cake. That was a very good day.

Returning from my training in Nepal, I stop practicing yoga three times a day and fall into a really bad depression. In the middle of my hopelessness, I meet Ryan. He tells me ‘you need to breathe,’ and he just sits there and breathes so calmly and deeply that I have to breathe with him. Ryan is like a beacon of light, guiding me through the vast oceans of my sorrow. He teaches me to trust, to love and truly connect again with another human. My walls come down and I let him see me, but only the parts I have let myself see.

One day, lying in Ryan’s arms, I announce, “I’m going to change my hair.”

As soon as I say this, my heart starts beating quickly. He has only seen me with my twists and I worry what his reaction will be. My struggle with my hair is one of many that I keep in a locked box. I have not been “natural” since a young child. My mom has learned how to do this crochet weave in style, one that will change my twists to free flowing natural-looking curls. She says I need a change, and I reluctantly agree.

Ryan smiles, “Yeah?”

“I’m excited,” I lie and he agrees.

But when it’s done, he doesn’t like it. His hands awkwardly pat my weave of ringlet curls.

“It’s so big,” he says.

“I don’t know if I like the fake curls,” he says.

“Why don’t you go natural?” he says. “How do you wash that anyway?”

His words sink into the pit of my being. Now the box is open and I’m bombarded with flashbacks. The white customers when I worked at Shoprite asking the same questions, making the same statements in condescending tones.

“How long does that take? It can’t be all yours. How do you wash it? Can I touch it?”

I don’t get why my hair seems so exotic to them. Haven’t they seen other people wearing these styles? I feel like a spectacle. An animal at the zoo. I try to summon the courage, gather the words to express my relationship with hair, one of the most hated and loved aspects of my blackness. I see Ryan as another white male who will never understand. All the love we share and he will never understand. I remember his statements about being colorblind and wonder how he sees me? Did he forget I was black? Did my disappearing act work better than I thought?

“Don’t shut down on me,” he says.

My friends told me this would happen, that he would not understand. “It’s ingrained,” they said. “Implicit bias.”

They tell me “Your new style makes you look more black, that’s his problem. He just got comfortable and forgot you were black.”

“You’re putting up a wall,” he says, and I was.

Weeks pass before I remember my decision to be seen, to be true.

One night, over dinner with Ryan, I open the box. I say “You asked me to go natural but you don’t understand this is a battle I have to get through.”

I tell him what I went through in school, constantly perming my hair to make it straight until I got braids. How random people want to touch my hair or ask me, ‘‘How do you wash your hair?”

The same ignorant question he asked me. I tell him that my hair is a part of my blackness that I both love and hate. The shock on his face is almost comforting. Maybe what everyone said about him is not true. We speak about intentions, other microaggressions, my feelings on black hair, on blackness. As I see me, he sees me.

He says, “I just want you to feel free and be yourself. If this makes you happy that’s all I want.”

“I love you,” he says.

I start to feel that I can trust him and trust his intentions. I can’t always expect him to know things but when I do talk about these things, he really listens to me. We can communicate through this.

I don’t have to run away and I don’t have to disappear. I am learning to love me, my body, my hair, my blackness, my soul.

Would you like to see the full production of Black Stories Matter: Truth to Power? Download our Viewing and Discussion guide and host a viewing party! https://tmiproject.org/host-a-viewing-party/