Graduating from college during a pandemic was anticlimactic in many ways. Instead of the big family party we had planned, my parents and I ordered takeout to celebrate the night after my senior thesis presentation, which I delivered on Zoom from my childhood bedroom.

Continue readingAlone Together: Fred Brill

It is not that living through a pandemic was prompting an existential crisis. I simply felt a profound need for something new in my life. I needed to feel free again.

Continue readingAlone Together: Tracy Raczek

– Tracy Rączek (she/her)

“A tear in cloth can be too large for a patch” says the Pashtun proverb.

Recalling his UN fieldwork in a country where peace and economic prosperity seemed impossible, my colleague’s fingers turned stiff to gouge a pretend hole in his pants. Failing to stitch it, he slouched, wearied by his pretend loss and too real recollections. “See? The damage is far beyond repair.” My heart hurt for the country. As I walked away, I also selfishly wondered how many ruptures in my life had I made that were too deep to mend.

I do damage. I do damage because I am stubborn. My stubbornness leaves me with broken bones, abandoned relationships, and lost jobs. Yes, I am the kind of stubborn that has carried an injured man down a mountainside and fought bosses that sexually harass. But I also struggle to genuinely apologize, even when I know I am wrong – even to those with whom I am closest and love the most. So when she called last April – that precious old friend whom I had faulted and not spoken to 20 years since – Covid was the perfect scapegoat to remain silent.

At the start of this pandemic, we were pounded in NYC. TV and radio ceaselessly poured reports of the rampaging disease and skyrocketing deaths into our apartments that we paced within. Temporary morgues stacked up in alleys and parks around us. Family, acquaintances, and colleagues fell ill; some died without warning. We consoled each other across the ethernet; across the airshaft of our tenement building. Boarded streets fell eerily quiet except for sirens that screamed by our windows, then echoed down the city’s canyons.

I stopped listening to the news, picking up calls. Stopped listening to anyone. I was never good at listening to others anyway. In March I was walloped by chest pains and a positive Covid diagnosis; trapped inside a baton-beaten one-tonne body, I was forced to fight for my breath – a fight I nearly lost and try my hardest to forget.

“Just calling to check you are OK in NYC — with the virus and all,” a slight strain in her gentle voice. She was “that friend” in your twenties, when you are joyous and foolish; bold and broke. She was sweet. I was wild. In our tribe of musicians, ski-bums and vagabonds, she and I were inseparable for years and made a point to weave our days and lives together — steeped like tea. I can’t recall which joke was hers or mine, only memories of howling together hiking under a full moon in the mountains; searching for a water-hole in the desert; living in adjacent rustic cabins by mossy woods in Alaska. It was there, in Alaska, that our friendship fell apart. In an art gallery, over a glass cabinet full of Russian stacking dolls, during a fight of my making, I ended our friendship.

For the next 10 years or so, we did not speak. Eventually written words, on holiday cards, were slipped under the wall that I had built between us. Hers were always colorful, with hand drawings of Alaskan wildflowers, tales of huckleberry picking, well-planned river trips, pictures of her children. Mine dripped with political sarcasm and adventures that too often ended in bike crashes or nearly sunken boats. Both tinged with a hint of longing.

Now she was on my phone. I pressed “voicemail”, like an obsessed lover, and listened to her message three times. “Just calling to check you are OK in NYC — with the virus and all…” By this time, in April, I had escaped from the city to my tiny off-the-grid Catskills cabin. Heated by a woodstove, without electricity or running water, and tucked into 45 acres of woods, I am ever grateful for it. Now it would allow me to walk without a mask and to rest – or more accurately collapse – whenever I needed. I did not have energy to call her back, reopen a deep wound and try to repair it. But something happens when you vomit on the ground, your mind spirals outward and you stay up all night fighting to breathe like you are drowning and you are not sure you will make it till dawn. Then you do – but you don’t know if and when it will happen again. You care more deeply about each small thing afterwards. Everything, achingly, matters. And, oddly, nothing does. Risk and vulnerability and values change proportion.

She picked up.

Sitting in my cabin, in the only spot with a mobile signal, staring out the window to the hill of trees, yellow-green with spring buds, focusing on my breath as we talked — something I must do more now — I let it out: “I am so very sorry for what happened back then in Alaska. I can be so stubborn. I am sorry.” Ever kind, she listed traits that she would trade-in for better ones. We chalked it all up to youthful stupidity and arrogance then dove appreciatively into each other’s insights of the world today. We mourned time together lost and belly-laughed over memories shared, trying to pry apart who said this and who did that so long ago — an impossible task. “Perhaps” she noted, “amid all the space of Alaska, maybe we were free to become more of ourselves and less of each other?”

Finally, after more than two hours passed, we rested on plans to meet as soon and as frequently as our lives allowed, once I am strong enough, and once we all feel safe enough to travel. Reluctant to hang up, reality pressed. Her pre-teen daughter was painting their Anchorage kitchen gold, unwatched and without a drop-cloth. Our Catskill cabin was getting dark and cold — the woodstove fire and lamps needed tending.

There is, of course, a very real chance we will not meet again. But she is kind and I am stubborn so I will mend best I can.

Alone Together: Katie Gomulkiewicz

Her hair, mostly a deep silver with streaks of peppercorn black, is pinned up with a blue rhinestone hair clip. My grandma glides out of the nursing home with a wicker basket and iPad in tow. I have come to expect this type of anachronism from her. Born in 1929, the year the stock market crashed at the beginning of the Great Depression, she was raised on a Mennonite farm in Iowa. The fifth of seven children, my Grammy Ida often told me, “that meant in the winters, I’d be on the outside of the bed and in the summers, on the inside.” She is ninety-one now, a far cry from the young, bold woman who drove a yellow VW bug around Europe after college. And yet, her spunk hasn’t diminished. On this day, in 2020, I have come to “jail break” her from the nursing home in Portland.

As I waited for her (mask on) outside the doors of the nursing home my mind traveled back over the last twenty-six years of memories. My Grammy Ida has always been my best friend. We bonded at a young age over a mutual love of toasted bread slathered in butter; “the butter gals” our extended family would call us. How could I forget the time, many years later, when she taught me to butterfly and stuff a guinea fowl with olive tapenade (the perfect first date meal, she claimed). I could never understand the logic of crushing the bones of a tiny, dead bird as a good first impression, but she insisted. When I moved away to North Carolina, I worried about her. My other grandparents died while I was away and Grammy Ida got older and older.

Four years ago I moved back to Washington which didn’t please her, “why not Portland?” she’d always ask me. But it was close enough to take the bus on weekends to visit. We had become regulars at the Great Clips, the Costco, and the local pizza parlor. Then a year ago “it” happened. At ten am I had boarded a bus back to Seattle and at six pm I got the call from my Aunt, “Grammy Ida is having a stroke.” For weeks she couldn’t sit up and her words were a jumble of misnomers and misspeaks. I worried. I visited. I waited. My Grammy Ida was the first in her family to go to college. She raised four children as a single parent while working as a substitute teacher and tax accountant. She nurtured the family pets: a monkey, two parrots, countless dauchunds, a duck, and a one eyed tomcat named Sugar. She was tough as nails.

Now, a year later as I watch her walk out of the nursing home, I consider it to be a small miracle, but not an unexpected one. I greet her with a hug (which admittedly, may not be COVID-smart) and guide her into the passenger seat of the car. “Hey Grammy,” I say, loudly so her hearing aids can pick up the words. For the past few months, she’s been confined to her small room which is wise from a health standpoint but painful to a ninety-one year-old whose greatest joy in life is visitors. But today, on her birthday, I’m here to take her back to the house she lived in for fifty-three years in Portland for banana cake (her favorite) and steaks.

There is so much pain and uncertainty in the world today. Grammy Ida as lived through her fair share of pain and uncertainty: the Great Depression, World War II, Vietnam, and now, COVID. On a bad day recently she asked me, “is Germany still in two parts or one?” “It’s one Grammy” I told her, “and has been for a few years now.” She paused and thought for a moment, “that’s good to hear,” she told me “that’s good to hear…” I told my Aunt about this encounter later in the day and we both laughed. But my sister had a different reaction. “Katie,” she said to me “can you imagine how much has changed in Grammy’s lifetime?” she reminded me and as usual, she is right. COVID-19 will make it into the history books, that is for sure. And I imagine that historians will have much to say about its impact.

My Grammy Ida will not make the history books, but she should. These last few months I’ve temporary moved to Oregon where I can go visit her frequently and bring her homemade carrot cake and large oranges from the grocery store (which are always her favorite gift). Her life has not been easy, but it has long and full of many memories. A few years ago, on one visit to Portland, I drove us to a local donut shop. We pulled up in her old silver Toyota in our matching red sweatshirts and Adidas sneakers (to the amusement of everyone inside). I got a yeast glazed donut and she got a chocolate one. We drove to a small park by her house and ate the donuts on a bench by a pond with ducks drifting across the water. I don’t know how many years or months or days my Grammy Ida has left, but I will cram in as many memories as I can. And in a funny way, thanks to COVID, I already have. As I drive Grammy Ida back to the nursing home after her birthday party I give her a kiss on the top of her head and say, “bye best friend, I love you.” “Love you more,” she replies. “Not possible,” I retort.

My Grammy Ida will not make the history books, but she should. These last few months I’ve temporary moved to Oregon where I can go visit her frequently and bring her homemade carrot cake and large oranges from the grocery store (which are always her favorite gift). Her life has not been easy, but it has long and full of many memories. A few years ago, on one visit to Portland, I drove us to a local donut shop. We pulled up in her old silver Toyota in our matching red sweatshirts and Adidas sneakers (to the amusement of everyone inside). I got a yeast glazed donut and she got a chocolate one. We drove to a small park by her house and ate the donuts on a bench by a pond with ducks drifting across the water. I don’t know how many years or months or days my Grammy Ida has left, but I will cram in as many memories as I can. And in a funny way, thanks to COVID, I already have. As I drive Grammy Ida back to the nursing home after her birthday party I give her a kiss on the top of her head and say, “bye best friend, I love you.” “Love you more,” she replies. “Not possible,” I retort.

Alone Together: Kathryn Reale

– Kathryn Reale (she/her)

It is currently 5 am. I have been up since 4, plagued by the information I now carry with resounding devastation and anxiety. What I had anticipated over the last 10 days has unfortunately been reassured with a simple byline of a test result: I am positive for COVID-19.

Over the last several years, being sick has been part of my daily life. When you spent as much time on airplanes as I did, it really came with the territory, and I knew the associated risk. In 2019, it was necessary to keep my job, my relationship & my sanity, logging more than 60,000 miles in 8 months. Spending that kind of time in public places, sharing the same air with so many different people, it was a small price to pay to live. From all the respiratory infections, touches of flu, colds, & sinus infections in the last seven years…nothing has felt more sobering than this diagnosis.

Now – I will be the first person to admit when I am in the wrong. Or better yet, being dramatic. And to put you at ease, I am not dying. Although not being able to taste my food or hug my boyfriend or see my family makes me certainly feel down. The more significant reason I am sharing this with you today is that I was wrong. About everything. When our country went into lockdown in March of this year, I honestly felt one emotion, which was disappointment. Disappointed for all the missed social gatherings, the weddings that were no longer happening. My boyfriend and I met at a wedding after all, and I have always loved being in large groups celebrating with others. The social butterflies of the world can empathize with me; it was a challenging few months. However, I knew people were dying, but there was honestly so much information out there with a division so strong, it was virtually impossible to keep straight. Watch the news, don’t watch the news, COVID isn’t real, I’m anti-mask, please wear your mask, I have a condition that prevents me from wearing a mask, I could go on for days.

So with this information, I opted to continue living my life when the world opened up. Dinners with friends, boat gatherings for birthdays, bridal showers, road trips through National Parks; you name it, I did it. I am a healthy 28-year-old. As long as I wash my hands and conduct proper hygiene regimes, I will be okay. I was wrong.

I was met with a brutal confrontation with reality when a friend of mine found out that her parents had tested positive for COVID-19. She had seen them on Monday, had been with them for most of that week, returned home on Saturday, and had driven down to see my boyfriend and me on Sunday. She tested positive the next Tuesday. I know this by heart because you have to know. These questions were the primary subject the doctor implored me on a zoom call that day. After I had naturally wiped the tears enough to connect with a physician. He carefully explained that I had to wait and quarantine for at least 7 days before I tested for COVID if I did not start to show symptoms. “Symptoms can show up as late as a week to 14 days after exposure,” he said thoughtfully, “I suggest you rest up and distance yourself from others until at least Sunday.” I was so careful, I thought. I was healthy, I made sure to use hand sanitizer. I was wrong.

I immediately called my boyfriend in a panic, unsure what to do as he was at his job where he worked in a lab with others, “exposing even more innocent people,” I thought. He assured me that we would get through this and promptly came home 20 minutes later, supportively sitting by my side as I rapidly googled scientific research on the virus. And the next three days went by, feeling a whirlwind of anxiety, stress, grief, anger, and restlessness to find out if the inevitable had, in fact, occurred. Until I started feeling a soreness in my throat 5 days into our quarantine. We received nose swabs on day 6, “am I starting to feel congested?” I said to myself that afternoon. On day 7, I woke up to my boyfriend making me breakfast. Little did I know it would be the last meal I could taste for a while. Day 8 brought the fatigue and headaches, and on day 9, shortness of breath when walking up a flight of stairs. I was wrong about everything.

What you do today matters. What you do today impacts everyone around you. From the kind older grocery store attendant who takes your credit card to the person you fall asleep to and wake up with every morning, your actions impact everyone around you. The world has been the most divided I have ever seen, and there are so many facets to that statement. But the greatest one for me is that we are selfish. I was selfish. I put my necessity to be around people before the health of the people around me. And for that, I am incredibly sorry. There is no one to blame here but myself. And at the end of the day, people are and will continue to succumb to this virus.

What I will leave you with is a salient but straightforward reminder to put others before ourselves. Kindness is exceptional and rare, and this virus has given us a unique opportunity to show someone that they are appreciated for staying home. For wearing a mask. For educating yourself. For displaying to the world that you care about the people around you. Somewhere in 2020, this sentiment has gotten lost. I am here to tell you it is very real. I am here to tell you that I was wrong about everything.

Be well,

Kathryn

Alone Together: Jaymon Bell

– Jaymon Bell (he/him)

The COVID-19 Pandemic really taught me that it is not physical distance that causes me to lose touch with my friends from the past. It is my failure to manage my time in an efficient manner in order to make a phone call or zoom session to catch up with them. I am never really too busy to pick up the phone and call someone.

The validity of that excuse faded as each day of quarantine exposed how much free time I actually had. It also was further eroded the more and more I saw Facebook posts from my fellow Veterans doing the 22 a Day Push-Up challenge for awareness on Veterans suicide. The statistic is that 22 Veterans commit suicide on a daily basis. The question kept lingering in my head, “Had I done anything to check up on my Brothers and Sisters in Arms during this pandemic?” That’s when I picked up the phone and called my Army Buddies that lived in the DMV.

I was able to reach five friends of mine that I have had since I attended Basic Training at Fort Benning, GA in the summer of 2002. After the phone call we created a Facebook chat in which we all decided to meet up at Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling the first weekend in June. I couldn’t help but remember how I felt that fateful summer in 2002 at Ft. Benning, Georgia during my drive up to see all of the guys. I was ending my first attempt at college after two successful years and two mediocre ones at the University of Tennessee. Most of the guys I was at Basic Training with were fresh out of High School and 1/3rd were still in High School and completing their training the summer between their Junior and Senior years.

My memories of Basic are vague at best but I do have a vivid memory of meeting one guy in particular, Jackson or “Jip” as I called him. You do not go immediately to training when you arrive at Fort Benning. There is a week in which you receive your first military haircut, vaccinations, and military clothing. That first week is such a strange time as you are in total limbo and trying your best to remember exactly why you want to be there. One evening that first week I was approached by, Jackson, who was 17-18 years old at the time, asking me in his slightly stuttering voice, “Hey, hey man, how do you shave?” I took out my shaving kit and showed him what I, as a previous once a week shaver, knew about the process. We now were faced with completing the daily task as fast as we could at 0445! Which did not add in any way to the discomfort. Less than 4 days later, Jackson and I were completely immersed in our new vocations and training every day on how to become Army Soldiers.

I lost touch with Jip until the late 2000’s when everyone was getting on Facebook. He had left the Army in 2015 and joined the Air National Guard. But as providence would have it, I was telling this same story around the table with my other basic training friends. One of the guys said, Jackson lives in Baltimore just a ways down the road from me. I then took out my phone to see if I still had his number in my contacts. I hesitatingly called the number I had and sure enough, old Jip picked up!! We caught up on things quickly and added him to the Facebook group chat that was started before this last get together. We agreed to have another get together so that he could see everyone again.

That first meeting of five turned into the second meet up in which we had two more veterans join us for dinner. What made this second meeting even more momentous was the presence of one of our Drill Sergeants! The one in particular who tormented us the most with push-ups and mule kicks during some of the hottest Texas days I have ever endured.

I am almost certain that this would not have taken place were it not from all the introspection caused by the COVID-19 quarantine. It was so rewarding to come together as brothers in arms after 18 years and hear the great stories of those of us with families and those with storied Army careers. We have all now re-established that bond that we forged so many summers ago. I hope and pray that none of us ever has thoughts that could lead to suicide. We at least all know that we have six other brothers willing to drop what they are doing and lend an ear to keep the enemy within at bay.

Alone Together: Isa Nye

– Isa Nye (she/her)

My mother-in-law arrived last week, a box of ashes. In the last voicemail I have from her, she’s telling me about the train tickets she bought to come visit. She splurged on a sleeper car. But that trip would not happen. She felt ill. My father-in-law drove her to the hospital. She didn’t leave. I can still hear her voice on the phone, straining, pained, “I have Covid.” She died in the ICU.

This wasn’t the way we thought she’d arrive for her last visit, not as ash. We gather around the box, and imagine her with us, picture her smile, her love. She was always so happy to be with us in our home. We picture her stirring soup in the kitchen, curled up on the couch with a book, painting a picture with the grandkids at the table. We picture her ready smile, her laughter, imagine her hugging us.

She’d had to cancel her flight tickets in March, waiting to come once the risk of Covid dwindled. We saw the numbers drop in other countries, but not here. They just kept climbing. We stayed in touch with phone calls and face times, but it hurt to be apart when we so wanted to be together. By now the US has more deaths than any other country in the world. That fact drops down heavy on me, more deaths than any other country in the world, her death one among them.

We didn’t get to be with her at the end. We spoke with a nurse who told us she would stay by the bed so my mother-in-law would not be alone for her last moments on earth. The nurse cried on the phone when she told us this. She had recently lost a family member to Covid too, and could not be at their side to say goodbye. She knew our pain. It was not the goodbye we imagined. We place the ashes on the shelf. We ache with the hole in our lives where she had once been. We picture her here.

We put on the masks she sewed us to run our errands. We picture her sewing them. We dream of hugging family again, of mourning together. We moan momma in our minds. Momma, momma, momma. Momma, we miss you.

Alone Together: Frank DeLucia

I admit I was quite angry when I first learned my wife Michelle and I had COVID– angry at Patty for having a birthday party, angry at the guests for arrogantly not wearing masks, angry at whoever it was who infected us, and even angry at Michelle for suggesting going to Florida in the first place.

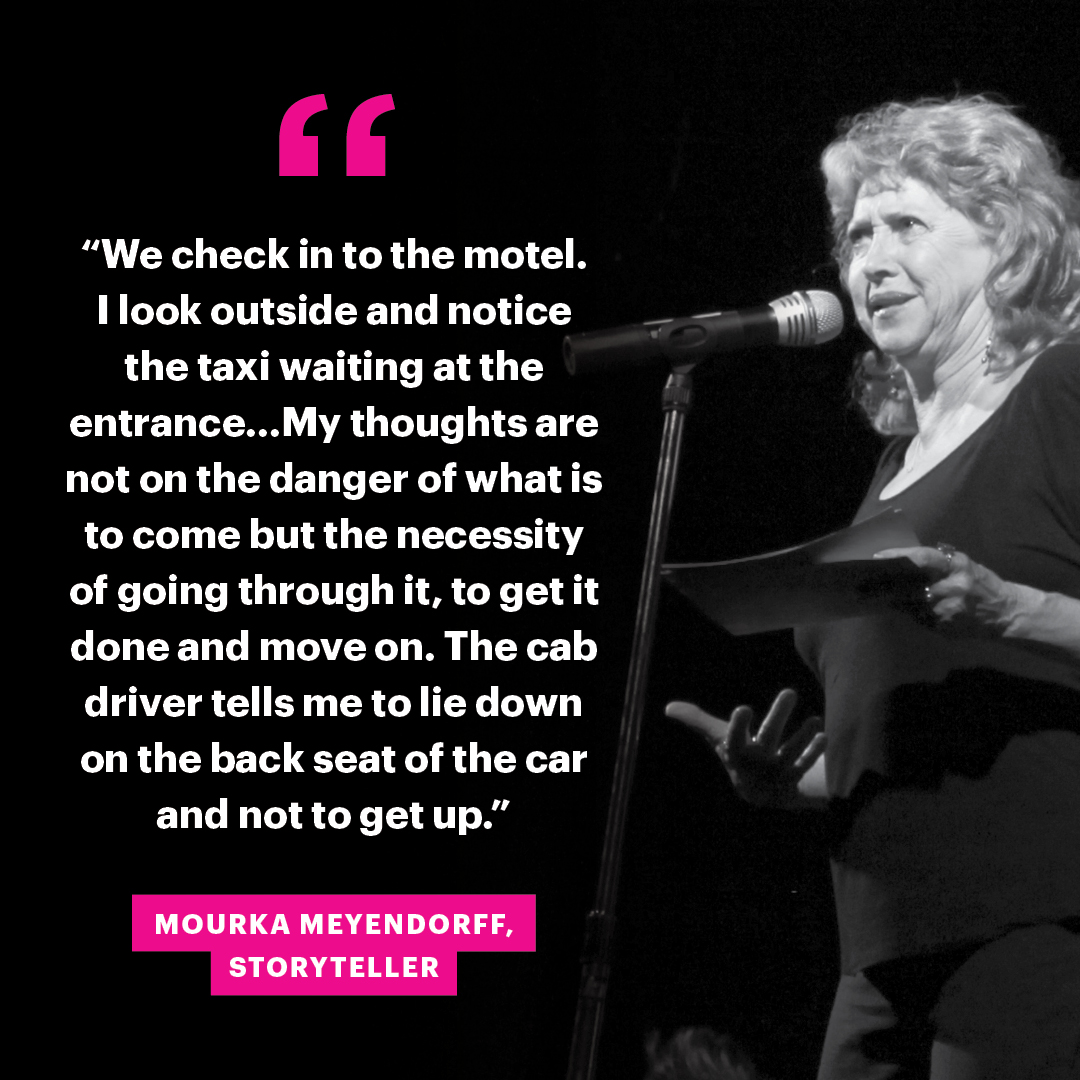

Continue readingThe Lucky Ones: Mourka’s Story

By Mourka (she/her)

I was 19-years-old in the fall of 1966 when my friend Barbara and I drove my two-tone 1956 Chevrolet to Baltimore, Maryland, where I was to have an illegal abortion.

One afternoon, a few weeks prior, I had returned from school, pulled into my driveway, parked, and stepped out of the car. I was loaded with books and bags and papers. Suddenly, Bo, my ex-boyfriend, was right there. I screamed from the unexpectedness of him. He was angry; I broke up with him. He grabbed my arm; the books and papers went flying. I thought he would kill me but instead, he ripped my clothes off and raped me on my car’s hood. Right before he got into his car and drove away, he banged me on the head. I never saw him again.

I slid off the car and fell into the dry brown leaves. I dressed. With leaves still in my hair, I slowly walked up the apartment steps where I lived with my parents. My father greeted me when I walked through the door.

He asked me in Russian, “Как поживаешь?” How was I doing?

I answered, “Нормально, всё нормально.” Everything is fine.

After swallowing many quinine water glasses and drinking vast amounts of alcohol in failed attempts to abort, I managed to obtain $500 from a friend for the abortion. Barbara and I scraped up the rest of the money for a hotel room and gas — there was not much left for food — a minor consideration.

I had the instructions memorized. I was to go to a certain Howard Johnson Motor Lodge in Baltimore. I was to check-in, get a room, and wait for a taxi that would pick me up at a specified time. I was instructed to be alone. I was not frightened. I was in deep denial of the danger that awaited me.

It was dark when we got to the Howard Johnson. We checked-in. I looked out the window and noticed a taxi waiting at the entrance. It was time to go. Barbara and I hugged and I walked alone, down the hall, into the lobby, out the door and climbed into the taxi. I felt like I was moving in slow motion. My blinders were on. My thoughts were not on the danger of what was to come but the necessity of going through it, to get it done and move on.

The cab driver told me to lie face down in the car’s back seat and not to get up. I did as I was told. I felt the taxi winding around curves and going uphill. About twenty minutes later, we stopped at a dark house. He told me to go in. I was greeted by a woman who asked me for the money. She took the envelope of cash and told me to go into an adjacent room, take off my clothes and put on a paper dress. I went into the room and there was a woman lying on her side on the bed in one corner, groaning. We didn’t speak. I didn’t want to know.

I soon walked into a very bright room and was told to lie down on the cold metal flat bed and put my feet into the stirrups. My legs began to tremble. The doctor and nurse were wearing sunglasses. The operation began. The doctor told me that there would be cramping but I was not given anything for pain. As it intensified I felt tears rolling down my cheeks. The procedure lasted fifteen minutes but felt like an eternity.

And then it was over.

The doctor asked me if I wanted to see the fetus. I said no. I was led into the original room. The woman was gone. I was told to lie down for a while that they would come for me. It was in this quiet moment that I realized what just happened. I could bleed to death. I could get an infection. Would I see Barbara again?

In about twenty minutes, I was given some pills for the bleeding and some menstrual pads. I got dressed and slowly and painfully walked out of the house and into the waiting taxi. Again, I was told to lie face down on the back seat. Also, I did as I was told.

Finally, the taxi dropped me off at the Howard Johnsons. I walked down the hall and was so relieved to see Barbara rushing towards me. We hugged. It was over.

The next morning, I wasn’t bleeding too badly. My angels were working overtime. I was going to make it. Some women die. I was one of the lucky ones.

• • •

Mourka wrote and performed her story as part of TMI Project’s 2013 production, What to Expect When You’re NOT Expecting: True Stories of Slips, Surprises, and Happy Accidents, a collection of true stories centered on the ways people exercise freedom of choice when faced with an unplanned pregnancy.

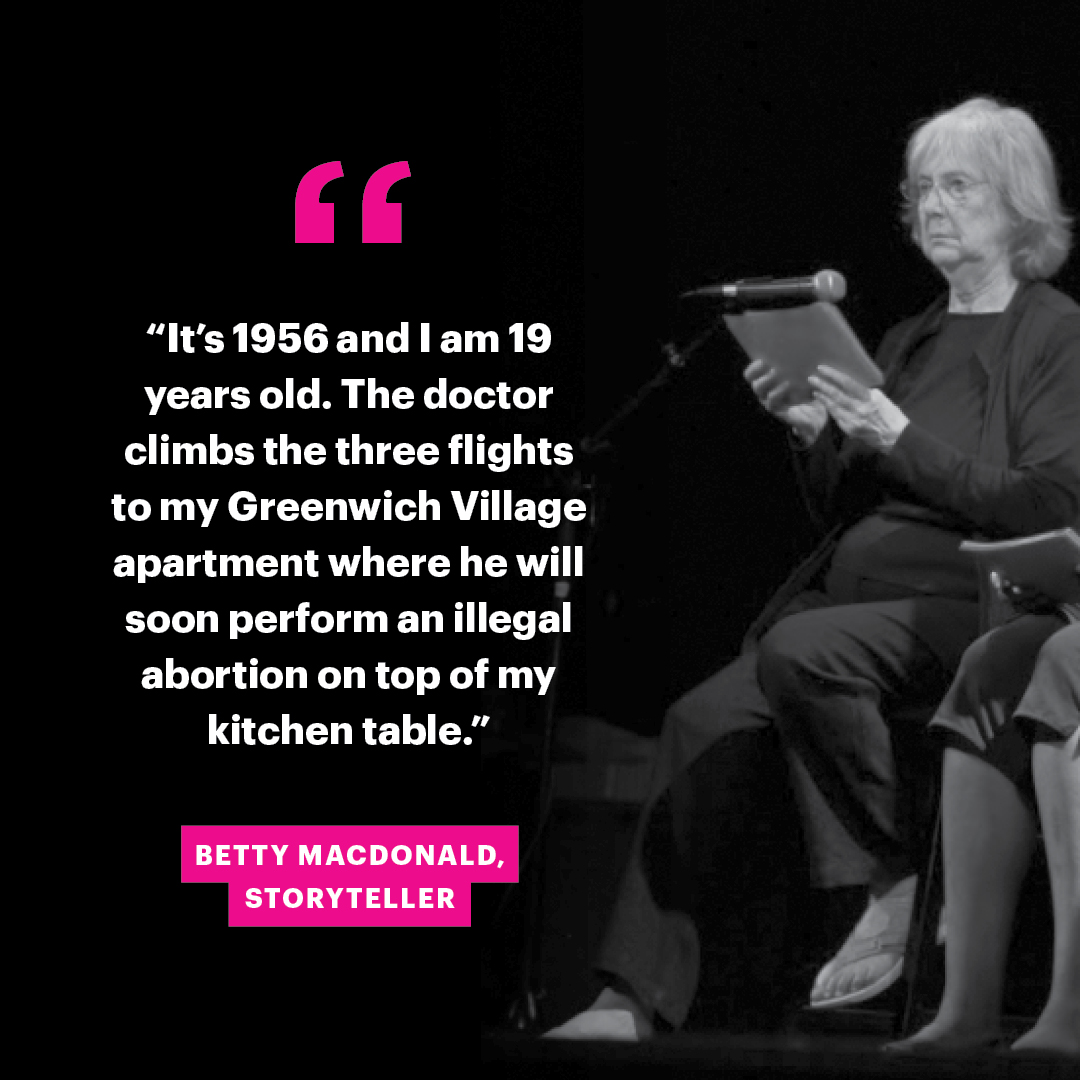

The Lucky Ones: Betty’s Story

BY BETTY MACDONALD (she/her)

As an 18-year-old girl in the early fifties, I possess very little knowledge of my body or reproduction. It will be twenty years before The Supreme Court passes Roe v Wade into law, making abortion legal. Not only is abortion illegal, so is contraception in many states. Not until 1974 does contraception become legal for unmarried couples. I know where babies come from. That’s about it. For a long time, I believe I am too skinny and too anemic to get pregnant. It’s my magical thinking.

After college, writing radio copy and hosting an afternoon disk jockey show on the local NBC affiliate, I spend a year in my hometown. I have total control of what I say on-air and what I choose to play, but I’m not allowed to touch the turntable or the microphones because I’m female. My co-host Charlie operates the control board.

After a year on air at the radio station and evenings working backstage and performing in the newly created theatre at the Virginia Museum, I take the night train to New York City, intent on studying acting.

In the Village, I become part of a group of struggling actors, artists, writers, and musicians who hang out in the coffee houses on Bleecker and MacDougal Streets. My boyfriend Joel was celibate for six years in self-imposed penitence for impregnating his first girlfriend when he was sixteen. When we get together, I almost immediately miss my period. The theory is Joel’s years of celibacy have intensified his potency. His super post-celibate sperm has overcome my magical thinking. I am pregnant.

Dr. C., my primary care provider, upon hearing my plight, places me in the care of his loyal and knowledgeable nurse. In turn, she puts me in touch with an abortion provider, a doctor who, after losing his medical license for preforming the illegal procedure, makes his living renovating apartments.

Joel, always the gentleman and the only man in our crowd with a steady job foots the bill — $500 cash. The operation will take place in my third floor Greenwich Village walk-up. My friend Claudette, a young woman toughened by her childhood in Nazi-occupied France during the Second World War, offers to be with me.

The doctor, having climbed the three flights, appears at my door slightly disheveled. At first, he surveys the apartment with a contractor’s eyes and offers some suggestions for possible renovations before unpacking his physician’s bag.

I lie down on my green and beige enameled kitchen table. There are no stirrups, so my legs and butt are placed in a mesh harness. The doctor considers anesthesia or pain medication too risky. I undergo the procedure without them. Claudette faithfully holds my hand as promised. She doesn’t freak out when I start screaming and talks me through the excruciating process. For weeks afterward, I bleed and feel faint.

I continue to date Joel and quickly get pregnant a second time. I don’t know how to prevent it.

This time the abortion doctor gives me instructions to meet him at an apartment in one of the many high-rise complexes in Queens. Another friend, Lorraine, offers to drive me, but because my instructions are to arrive unaccompanied, she waits for me in the car.

Before going in, I swallow a pill Dr. C. has given me to lessen pain. I take the elevator to the sixth floor. Just as I am about to press the buzzer at the designated apartment, a door on the other side of the hall pops open. The doctor pokes his head out and calls to me urgently in a hushed voice.

Once inside and on the table, I attempt to take a second pill Dr. C. has prescribed, but my abortionist stops me. He’s not taking any chances. Fortunately, the first pill removes me from the pain’s immediacy, although it doesn’t eliminate it. I experience the agony repeatedly, but this time it’s as if it’s from a distance.

When it’s over, Lorraine drives me back to West 10th Street. I break up with Joel and feel restored. I vow to be more careful in the future.

• • •

Betty wrote and performed her story as part of TMI Project’s 2013 production, What to Expect When You’re NOT Expecting: True Stories of Slips, Surprises, and Happy Accidents, a collection of true stories centered on the ways people exercise freedom of choice when faced with an unplanned pregnancy.